The Creative Classroom by Mitchell Lopate, M.A.T. = Academic humanities advising-mentoring, tutoring, writing support: "Fluid Learning." Two decades of college & university and middle-elementary education in-class/online with a B.A. in psychology and a masters in education. Cross-curriculum humanities concepts, career counseling, MBA instruction, composition and research methods, and values, ethics, and writing. mitchLOP8@yahoo.com / 840-216*1014

Friday, October 12, 2018

Monday, October 8, 2018

Sunday, October 7, 2018

Sunday, September 30, 2018

Saturday, September 29, 2018

Monday, September 10, 2018

Sunday, September 2, 2018

The Creative Classroom Experience book (c) 2018

Here's the table of contents:

----------------------------------------------------

1.

Commentary

on the Creative Classroom Experience: p. 9

2.

“Welcome

to the Creative Classroom”: p. 12

3.

Ground

Rules and Principles of the Creative Classroom: p. 17

4.

The

Creative Classroom Mandate: p. 21

5.

Grammar

– Fundamentals of Reading and Writing: p. 25

6.

“Use

to/Used to”: p. 27

7.

English

is a crazy thing: p. 29

8.

Lay or

Lie?: p. 35

9.

Numb

about Numbers?: p. 37

10. Homophones, homonyms, Synonyms, and Antonyms:

p. 38

11. The Perilous Points of Punctuation: p. 41

12. Conjunction Junction, what’s your

function?: p. 44

13. Underlining and italics:

p. 46

14. Apostrophe marks show ownership: that’s

mine!: p. 48

15. That’s a Capital idea!: p. 51

16. Quickly qualify quotes!: p. 53

17. Clever, Crafty, Creative, and Calculating

Commas: p. 55

18. Writing is a good thing!: p. 59

19. Oh, no, it’s ‘the dreaded Outline’!: p. 62

20. THINK and brainstorm out your ideas!: p. 66

21. “A Thesis is a powerful statement,” I declared: p. 70

22. Who-What-Where-When-Why-How for a Thesis:

p. 74

23. Classic social archetypes (role models)

for a Thesis: p. 77

24. Four Motivating Factors of Society in

Literature: p. 79

25. The Creative Classroom Part II: a focus on

literature and short stories and writing: p. 86

26. Fluid Learning concepts for extrapolation

and juxtaposing ideas: p. 87

27. “What do you do well and how did you learn

this?”: p. 89

28. Topic Sentences are paragraph starters

(and cues): p. 93

29. Planning a Successful Tent Camping Trip:

p. 99

30. Learn to be a student: take notes and be

responsible: p. 102

31. Use transition words like a ladder for

successful writing: p. 106

32. Read good literature to develop critical

thinking: p. 111

33. “The Jungle” – a lesson in critical

thinking: p. 113

34. Using myth as a theme for a paper: p. 116

35. Odysseus: the man and the myth: p. 117

36. A myth: “A Modern Woman for the 21st

Century”: p. 123

37. Go to college and find yourself a career

and life: p. 131

38. Haven’t I seen you somewhere before?

Aren’t you famous?: p. 134

39. Bird Facts: p. 137

40. The Renaissance – an outline for 8th

grade: p. 140

41. Let’s Meet the Renaissance: p. 148

42. The Renaissance Guild Assignments: p. 151

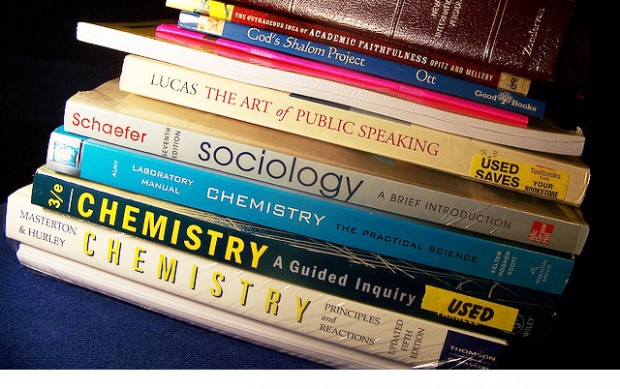

43. “I’m (not) Afraid of Public Speaking: p. 171

44. Poetry for Fun and Learning: p. 174

45. MLA & APA – how to cite information: p. 179

46. MLA & APA (and more) citation lessons: p. 182

47. Even MORE Citation help for MLA/APA: p. 185

48. Signal/Action Verbs show how an idea is

presented: p. 188

49. Sources for potential reading: science

fiction, humor, fiction and more: p. 192

50. “They Bite” by Anthony Boucher: p. 194

51. “The Veldt” by Ray Bradbury: p. 217

52. “Jim Wolf and the Wasps” by Mark Twain: p.

250

53. “Not Wasting a Watermelon” by Mark Twain:

p. 255

54. Great Builder: the Lady and the Brooklyn

Bridge: p. 260

55. “Manna From Heaven” – A one-act play: p. 273

56. About the Author: p. 296

Tuesday, August 21, 2018

Monday, July 30, 2018

Good versus Well: grammar lesson

Today's Lunchbox Lesson, c/o Analytical Grammar/Grammar Planet: GOOD and WELL

GOOD: an adjective, modifying/describing a noun. It's typically used three ways:

1. before the noun it modifies ("Have a good time!")

2. after a verb of being ("That movie was good!")

3. after a linking verb ("Those cookies smell good!")

1. before the noun it modifies ("Have a good time!")

2. after a verb of being ("That movie was good!")

3. after a linking verb ("Those cookies smell good!")

Good should not be used as an adverb to modify a verb.

It would be incorrect to say "I played good at piano practice today."

It should read, "I played well at piano practice today."

WELL: an adverb, modifying/describing a verb. That means WELL tells *how* something is done. For example, "She did well on her AP exam." (How did she do? She did well!) For example, "He reads quite well for his age." (How does he read? He reads well!)

**In certain cases, well may be used as an adjective and be interchangeable with good:

1. to indicate good health (I feel good/I feel well)

2. to indicate satisfactory conditions (All is good in the city today/All is well in the city today)

1. to indicate good health (I feel good/I feel well)

2. to indicate satisfactory conditions (All is good in the city today/All is well in the city today)

GOOD and WELL both change to "better" and "best" in their comparative and superlative forms.

This is a good research paper.

It is much better than your last one.

In fact, it's the best paper in the class!

It is much better than your last one.

In fact, it's the best paper in the class!

Everyone played well at the concert today.

The percussion section played better than the string section.

The brass section -- with the saxophone solo -- played the best!

The percussion section played better than the string section.

The brass section -- with the saxophone solo -- played the best!

GOOD is always an adjective modifying a noun.

WELL is usually an adverb, modifying a verb. It can, however, be used as an adjective only to describe good health or satisfactory conditions.

WELL is usually an adverb, modifying a verb. It can, however, be used as an adjective only to describe good health or satisfactory conditions.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Friday, June 22, 2018

Students develop School-Community Connections

PROJECT-BASED LEARNING

Mapping Their Futures: Kids Foster School-Community Connections

Students at the Y-PLAN project create bonds through grassroots city planning.

By Sara Bernard

September 29, 2008

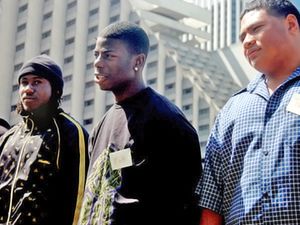

To help the two groups of students get to know one another, Y-PLAN coordinators ask them to give their names as well as something they appreciate about their own neighborhoods. A few mention the freshness of living by the water; others refer to the ability to walk to a grocery store or local basketball court. One young woman, toeing the ground, shrugs her shoulders and mumbles that she can't think of anything she likes about the gritty section of Richmond where she lives. "I don't feel safe there," she says. Others nod knowingly.

For inner-city kids who've grown up with poverty and crime, this sentiment is understandable -- and not unusual. Because the idea of neighborhood has as many negatives as positives, many Y-PLAN students admit to approaching their local project assignments with initial skepticism. But after twelve weeks of working in teams with UC Berkeley mentors to gather a big-picture view of urban planning, including conducting surveys and site research, crafting proposals for two community centers in their respective neighborhoods, and presenting their ideas to a panel of urban-planning professionals, Y-PLAN participants had a new sense of possibilities.

"Y-PLAN changed my perspective," says Julio Arauz, a student at Richmond's John F. Kennedy High School. "It's not just the negative aspect you have to look at. You have to look at the potential -- the bright side of things."

Through the knowledge that they, too, can affect their communities, Y-PLAN students came to some of the same conclusions as the program's founders: Young people have valuable ideas to bring to the city planning table, and educational revitalization can be a catalyst for community revitalization -- and vice versa.

Project: Transformation

Now entering its tenth year, Y-PLAN is "the heart and heartbeat of the Center for Cities & Schools," says Deborah McKoy, creator of Y-PLAN and the center's founder and executive director. Winner of numerous awards from such groups as the Architectural Foundation of San Francisco and the California Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools, Y-PLAN is held every spring for twelve weeks, usually in conjunction with ninth-, tenth-, or eleventh-grade social studies or history classes in hard-pressed East Bay communities. Graduate and undergraduate students in urban planning at UC Berkeley lead a rigorous project-learning curriculum; through initial brainstorming sessions to design sessions to formal presentations for city officials, high school students become stakeholders in the city planning process.

"After they critically analyze the places they are in," says Center for Cities & Schools program manager Ariel Bierbaum, "they learn the process by which those places get transformed -- and their role in that change process."

Past Y-PLAN projects include the redesign of the historic West Oakland train station and a neglected Oakland minipark. This spring, students at Emeryville's Emery Secondary School and in John F. Kennedy High School's Architecture, Construction, and Engineering Technology (ACET) Academy developed recommendations for two projects: a wellness center located in an unused part of the Emeryville school building (designed to serve as a youth and family destination for health and recreational services) and the Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center and Park, a cornerstone of an ongoing revitalization of Richmond's Nystrom neighborhood.

For city planners and administrators who'd been given the task of developing youth programming for the centers, Y-PLAN offered an opportunity to hear from the kind of young people who would be served by centers like these.

Many of the projects Y-PLAN students work on are so large in scale that any effect of the students' input may not be immediately obvious -- no train station or community center can be redesigned in a matter of months. Although student feedback has sometimes influenced city planning decisions, it doesn't necessarily sway them. Still, the overall impact the program has on both the student and professional perspective appears to be significant.

"Y-PLAN makes folks who deal with cities and urban centers aware of the incredible importance and value of public schools," says Deborah McKoy. "Urban public schools are often seen as 'the problem,' when in fact what I think we learn from Y-PLAN is how much a part of the solution they are."

The Finals

At the two schools' final presentations for city administrators, council members, engineers, and architects, students showcased scale drawings and three-dimensional models of each building, backed up by explanatory posters and Microsoft PowerPoint slides with detailed proposals for how the buildings might best be used. Richmond students emphasized the necessity for a tight security staff, a public gun drop-off, and social services such as driver's education, job training, a walking path, and a child-care center. They also proposed replacing a dilapidated playground with a garden or even a café to draw in more "customers."

Emery students presented their wellness center as a place to do homework, make art, use computers, and see counselors. To transform what they described as "a very empty and very dark" space, they incorporated in their design plants, murals, and large windows. They also had a variety of propositions for unused public spaces nearby that could be converted into parks.

Some site aspects students referred to, such as a lack of trash cans or a prevalence of broken gates, "frankly had me squirming," says Richmond city manager Bill Lindsay. "Why aren't we doing this? These ideas are simple and practical and can happen right away." Because budgets are chronically tight, many of the larger, more hopeful suggestions had little chance of coming to fruition in the near term, but the presentations nevertheless had a revelatory and empowering effect.

"Seeing what they want for themselves has been an honor," says Emery participating teacher Madenh Hassan.

"Y-PLAN is a good opportunity for us, because we can actually speak our minds," says self-assured Emery student Chantell Brown. She hopes the Emeryville center will be, among other things, a safe place where young people can go after school -- something teens in low-income, high-crime communities desperately need. She was eager to tell developers, educators, and city administrators "what the 'real' is, what we see every day, what we have to go through."

"Sometimes adults don't take us seriously," adds her classmate, Yesenia Cuatlatl. "Y-PLAN is a good idea because sometimes we say, 'Oh, they really need to change this,' but we don't do anything; we just talk about it."

Judging from the enthusiasm of their audience, the students' work -- and the determination that went with it -- helped adults take them very seriously indeed. As Bill Lindsay told students, "If you ever want to talk about city management as a long-term goal, please give me a call."

Y-PLAN is transformative, says Ariel Bierbaum, for both the audience (civic leaders and urban planners) and for the young presenters, who "gain facility with a new vocabulary and advocate for themselves in a civic space. Even though it's just a semester, from what I've seen, I think the kids hold on to that."

Ripple Effects

Many students do hold onto the experience -- and not just symbolically. As Y-PLAN introduces them to a spectrum of employment opportunities in urban development, planning, politics, and administration, some pursue related careers, many at UC Berkeley. "Without doing Y-PLAN, I don't think many students would have been exposed to those professions, or would even have known they exist," says Jeff Vincent, deputy director of the Center for Cities & Schools. Although the university is a local resource for these students, some do not see prestigious UC Berkeley -- or any college -- as a real possibility. Y-PLAN, which includes a tour of the Berkeley campus and tips on the admissions process, helps make college a more accessible option.

Y-PLAN has also had ripple effects nationwide: From 2000 to 2005, the Center for Cities & Schools worked with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to adapt the Y-PLAN model to HOPE VI, a public-housing-redevelopment initiative. In partnership with thirty-seven cities and more than 500 students, Y-PLAN coordinators led multiple-day "urban-planning boot camps," creating, says Deborah McKoy, "a national network of youth who live in public housing, and who then were a part of the redevelopment of their communities."

And in 2007, Alissa Kronovet, a former Y-PLAN mentor and a graduate of the city planning master's program at UC Berkeley, gathered students from both coasts to form the Young Planners Network (YPN) -- what McKoy refers to as "advanced Y-PLAN" -- an opportunity for students to attend planning conferences and network with students from other cities across North America. The YPN was created after Kronovet and an initial group of fifteen students from the Bay Area and Brooklyn met and worked with students from New Orleans at last year's Planners Network Conference. Participants were eager to continue learning, meeting one another, and, as YPN participant and Emery student Deszeray Williams puts it, "make a career out of helping make my community a better place." In April 2008, 100 people attended the first YPN conference, held in New York City, and a conference is scheduled in Berkeley for next spring.

Now that the program has been running for almost a decade, Center for Cities & Schools staffers have put together a "Y-PLAN Handbook," a step-by-step guide available to the center's school and community partners. Although Y-PLAN is a labor- and resource-intensive undertaking, its founders have high hopes for its scalability -- and, ultimately, for sustained, systemic change in communities and schools.

It's a daunting task, of course, but the Y-PLAN approach embraces one key idea: Start with the kids. "Even though we may not say it, we care about our community as much as adults do," says student Chantell Brown. "We did Y-PLAN so that we could have a voice."

SARA BERNARD IS A FORMER STAFF WRITER AND MULTIMEDIA PRODUCER FOR EDUTOPIA.

Monday, May 7, 2018

Friday, July 7, 2017

The March of the Dinosaurs (full movie)

A great movie about dinosaurs (both plant eaters and meat eaters)--and their habits and activities.

Monday, April 10, 2017

A word puzzle to reinforce critical thinking and writing skills

In teaching in a foreign country where pedagogy and instructional methods are quite different than Western methods, I have found ways to bring creative thinking and reasoning together: what I call “fluid learning”. To me, this brings both left-and-right brain styles of thinking together in one complete package. As an example, I used a simple word puzzle this week in my writing class.

My reasons were more than playing a game: it was serious from the start, because my Chinese students DON’T like to brainstorm or word-web out ideas. They just try to write in English, and in doing so, get bogged down and discouraged. But this lesson showed them a lot more than they expected.

First, I made up a word puzzle with business English vocabulary that they will likely encounter in their sophomore classes. Because I’ve taught this course as well, I know what words are commonly used on exams. In Asian countries, especially China, the emphasis is SO strong on “study-memorize-test”. There is no amount of critical thinking taught to the students. And I insist that they need this, especially as international graduate-degree-seeking young men and women.

Then I started the class. I knew they were apprehensive: their mid-term papers were due. And I wrote the word “test” on the board. It raised some of the tension, but then I wrote “con” in front of it: “contest”. It brought laughs and smiles. Yes, I said, this will be a fun exercise for you all, and you will learn to think and write in this lesson.

I gave out the word puzzle papers, FACE DOWN. That’s important: “DON’T turn them over!” I wanted them to learn to LISTEN to me first. Of course, within two minutes, several students had ignored me and begun to scan the paper. I stopped each time and mildly reprimanded them that “you need to LISTEN to me. If this was a job interview process and you read it and saw on the bottom that ‘Failure to listen means you are not qualified for the position,’ you’d be crushed with disappointment.” I reminded them that I wanted everyone to have a fair chance to be the winner of the contest. It doesn’t matter who has the highest grades, I said. This is different.

So then I signaled them to begin. And I could listen (even though I don’t speak Chinese) to their exclamations of surprise and delight when they found words in the puzzle. I watched their earnestness and determination as they pored over the combinations and searched for patterns. I observed them interacting with each other in pairs and groups as they shared results.

When the first person sounded out that he had completed all the words, the others kept going. I let them continue: their progress was part of my goal. I wanted them to complete the process on their own initiative. We took a short break, and I still saw some of them trying to solve the missing words. What I noticed was that some of them instantly could figure it, while others tried different ways of seeing patterns in the letters. And everyone had his or her own way of doing it.

As a follow-up, I wrote out the list of results and methods that I wanted them to think about for writing a paper about this experience. Again, as noted, my students are NOT the kind who do brainstorming. They are much more inclined to try and memorize something, or to use their cell phones to surf for an answer. And I gleefully told them at the start that they were welcome to use their phones—but that the device would offer no help. They had to learn to THINK first.

I put a title on the board: Solving the Word Puzzle. My students need to learn how and why a title should be on a paper. My reasoning is “What is the idea to be explained in the content? That’s the title.” Then I wrote out a numbered list of items that they had experienced in the process as a way of showing them how to WRITE DOWN ideas and use it as a focal point to bring up more examples of thoughts for the paper:

1. Think independently.

2. Work in teams; help others

3. Solve problems without directions

4. No phones needed—do this with your own brain power

5. Have fun—get excited!

6. Stay with an idea! Keep pushing for results and answers!

7. Listen first to directions!

8. Learn new vocabulary words

9. Learn word recognition

10. Not use “study-memorize” for results. Use creative-critical thinking.

11. Brainstorming ideas by writing them and seeing where they lead in other results.

My students thanked me and said it was really interesting. They enjoyed the class, and I reminded them that it’s just as important to THINK about writing and then to plan it out first—just like I had done for them with the examples that I listed.

I said that we will write about this experience and that this list will serve as reminders of how and what and why they learned something, and how to remember it. And then I thanked them for helping me learn to be a better instructor.

Tuesday, April 4, 2017

Get that Life! Follow your dreams to success!!

(The Creative Classroom says, “I am happy to say

Ericka is a friend of mine who has found success and her heart’s dream!”)

Get That Life: How I Turned a Failed Restaurant Into a Successful Food Truck

Ericka Lassair left a job that made her unhappy to create Creole-inspired hot dogs for a living.

By Heather Wood Rudulph – Cosmopolitan magazine

Mar 27, 2017

When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, Ericka Lassair left a successful job in finance to start a business that would help rebuild her hometown. She opened Diva Dawg, a Creole-inspired hot dog restaurant, in 2012 to local fanfare. A year later, competition drove her out of business, and Lassair took some time to figure out what to do next. Diva Dawg was reborn as a food truck in the fall of 2014. The business, which now includes the truck and a stall at a food market, has become a local hit, but Lassair has her sights set on national success.

Once I graduated [college] in 2001, I took a job with a finance company called Chrysler Capital to become a collections agent. The job was in Dallas and I was desperate to get out of Louisiana to see different parts of the country. After four years of cold-calling people about their late car payments, I started applying for different positions within the company. When an auditor position opened up that included frequent travel, I went after it. I spent the next two years flying all over the country.

At our main office, we used to do a lot of potlucks. It was the first time I discovered people outside of my family loved my food. I was creative with my dishes, which always had the New Orleans Creole flavor. I would get requests from coworkers to cook for their dinner parties; one of my coworkers would constantly buy my pies. I never considered cooking as a career before then. I thought, Who wants to be stuck in the kitchen all day sweating? Once people started requesting my food for their events, it got me thinking.

When Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, my parents and little brother came to live with me in Dallas. They thought it would be just until the storm blew over, but they couldn’t go home for eight months. They desperately wanted to get back to their life but I loved having them there. When they left, I felt so empty. I realized I wanted to be home in New Orleans. I started asking for assignments that took me to the city, and I would use my miles to fly home on the weekends.

I was moved up to become a retail credit analyst, the person who checks your credit when you buy a car at a dealership. I was stuck at my desk every day making calls or going through piles of paperwork. I was good at my job, but I was miserable. After a year, I knew I had to quit. My bosses offered me another promotion, [but] I turned in my company car, sold my house, and moved back to New Orleans.

Being home felt good. I got a retail job at Saks Fifth Avenue and tried to map out my plan. I was thinking of going into the food industry but I wasn’t sure how. I applied to a [two-year] culinary program at a community college and the prerequisite was to get a job at a restaurant. I interviewed at Commander’s Palace, which is a historic restaurant in New Orleans. I was intimidated but the chef gave me a chance. I worked in the dessert department making bread pudding soufflés earning $7 an hour.

I graduated from the culinary program in 2010. One day, I was craving hot dogs, and I bought some regular wieners and buns, and a can of chili. I added my Creole flavors to them and ended up eating them all week. The idea hit me to open a Creole-inspired hot dog restaurant. I started writing down recipes — like a chili dog with fried chicken, and a crawfish chili dog — and asked a friend of mine who owned a nursery for business advice. She recommended Good Work Network, which offers free small-business consulting. I started taking all the classes they offered. I discovered a small credit union that has a reputation for helping new business owners.

I knew I wanted to be on Magazine Street. It was always my favorite place to shop with my mom, and I love the architecture and boutiques there. When a spot opened up at the end of the street, I jumped at it.

That year at Jazz Fest, I was introduced to a vendor who had a sausage booth. I told him about my idea and he offered to make my hot dogs for me. I wanted something special, and when I tasted what he created for the first time, it was so good I cried.

Back then, I wasn’t really big on social media. I just spread the word by posting “Diva Dawg Coming Soon” on the door. I also took out an ad in a local paper. A lot of people heard about the restaurant from news coverage; I was getting a lot of write-ups from local journalists because another hot dog restaurant had opened across town, so now it was a trend.

I was so upset because I had been working on this idea for so long. I wanted to be the first. I went to eat there to see what they had to offer and it was nothing like what I wanted to do for Diva Dawg. They had basic hot dogs, sausages, and toppings. So I continued to move forward.

We opened in September 2012 and got a great turnout. The restaurant was packed. I could barely keep up. I hired one dishwasher, a cashier, and a cook. I trained my little cousin to help me with everything, and my boyfriend at the time and his two sons helped, and so did my mom. I was cooking, running the cash register, doing all the accounting, and talking to the customers. It was overwhelming, but I was so excited. I thought, We’re going to make it.

In March 2013, the other hot dog place opened up a new location on Magazine Street. The moment I knew I was in trouble was when a lady came in saying she left her credit card behind. Then she said, “Oh, it’s the other hot dog place.” My heart sank. It was a downward spiral from then on.

I KEPT A SMILE ON MY FACE, BUT INSIDE I WAS STRUGGLING.

I started borrowing money to pay the rent. I didn’t want to ask my family for money, so I took out those quick, high-interest payday loans. I couldn’t pay my employees on time. I’d have one good day but then a week of hardly any business. I kept a smile on my face but inside, I was struggling. I would go home at the end of the night and cry.

In September 2013, I applied and got into a program with the Urban League called the Women-in-Business Challenge. It’s an incubator that helps small-business owners sharpen their skills with classes and networking, and at the end, there is a pitch competition and a $10,000 prize. We talked about our struggles and these other entrepreneurs gave me a lot of new ideas. I was starting to feel hopeful, but I was three months behind on rent and my landlord was threatening eviction. In November, I made the decision to close.

I thought I would have to leave the Urban League program because I lost my business but they encouraged me to stay. The classes helped me release the stress and encouraged me to try again.

I went back to working in retail, which allowed me to make a little money, but I was broke. I was relying on my parents and taking the bus every day. I was hiding my car at the dealership where my little brother worked because I didn’t want it to get repossessed. How ironic that I started in collections and here I was, hiding my car.

I have always been an upbeat, positive person but the stress of entrepreneurship is intense. It’s a risk you are taking with not just your life, but your employees' and your family's.

Even though I was in a funk, I followed through on the Urban League program. The pitch [competition] was in March and I put everything into it. My revamped business plan was to do a hot dog food truck. Even before I opened the restaurant, I thought a food truck was perfect for my concept but New Orleans didn’t have clear guidelines for running a truck in the city. I didn’t want to take the risk of getting a food truck and then not being able to be in business. But after the restaurant closed, I decided to go for it, [and] I won the $10,000.

I reached out to a local bank owner I knew to see if he’d help me, and he said I’d need a business partner [because of my bad credit]. I reached out to my cousin-in-law Andre who always supported me. When he said yes, I started to worry, What if this doesn’t work out? I don’t want to ruin his life too.

We got approved for the loan, and my meat guy told me about someone who was selling their food truck and moving back to L.A. The timing was perfect. We cleaned the truck, painted it, and rebranded it. I wanted to open in October, which is National Chili Month. We booked every [local] festival we could find with that truck. That first month, I probably slept 20 hours total. I was determined. I was not going to fail again.

It was just me and Andre for the first month. He was a police officer at the time too, so he would be working 24 hours some days. I would hire people now and then to help me when he was busy.

After two months [in business], we had money saved, and that’s when I knew everything was probably going to be fine. With the restaurant, there was never any money left over. With the truck, I don’t have to pay rent and electricity and employees for eight-hour shifts that only see two customers. I needed a fire permit and a health permit. It was much more manageable. We mostly worked lunches, parking the truck near the hospital and some office buildings.

Our first Mardi Gras [in 2015] was the true test for me. You can’t drive in this city during the festival. I had to park the truck in our location four hours before they started to close the streets off. I had to do triple the amount of prep work. My ankles were swollen and I was sleep-deprived. I cried in the corner on the truck like a baby because I was so overwhelmed and stressed out. But it was a huge success. The experience taught me the importance of delegating. I needed to learn to let go, to allow myself time to work on the business while not running every aspect of it. I think 2016 was the first year I was able to start doing that.

In November 2016, we opened a [stall] in Roux Carré, which is a food accelerator [market] that helps small businesses. Now we reserve the truck for festivals, catered events, and parties. Our schedule is always random and unpredictable, and we can get a call to do a job the same day.

What I’ve learned is not to do things too fast. I write down all my ideas, but focus on one thing first and do it well. I want to make Diva Dawg a national brand, develop my own line of sauces and cookware, and even host a TV show. But I will first focus on getting into the airport, then malls. It’s just a feeling I have. With everything that I pursue in life I have a vision first, then I have to bring it to life.

Get That Life is a weekly series that reveals how successful, talented, creative women got to where they are now. Check back each Monday for the latest interview.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)