For 12 hours, two herds of wild South African elephants slowly made their way through the Zululand bush until they reached the house of late author Lawrence Anthony, the conservationist who saved their lives.

The formerly violent, rogue elephants, destined to be shot a few years ago as pests, were rescued and rehabilitated by Anthony, who had grown up in the bush and was known as the “Elephant Whisperer.”

For two days the herds loitered at Anthony’s rural compound on the vast Thula Thula game reserve in the South African KwaZulu – to say good-bye to the man they loved. But how did they know he had died March 7?

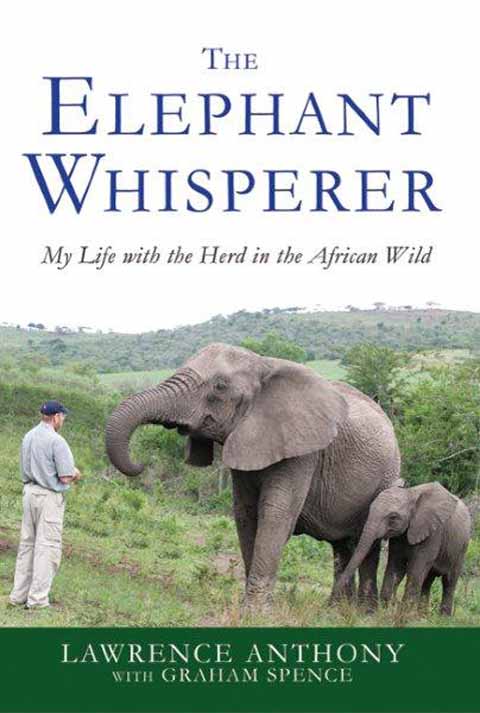

Known for his unique ability to calm traumatized elephants, Anthony had become a legend. He is the author of three books, Baghdad Ark, detailing his efforts to rescue the animals at Baghdad Zoo during the Iraqi war, the forthcoming The Last Rhinos, and his bestselling The Elephant Whisperer.

There are two elephant herds at Thula Thula. According to his son Dylan, both arrived at the Anthony family compound shortly after Anthony’s death.

There are two elephant herds at Thula Thula. According to his son Dylan, both arrived at the Anthony family compound shortly after Anthony’s death.

“They had not visited the house for a year and a half and it must have taken them about 12 hours to make the journey,” Dylan is quoted in various local news accounts. “The first herd arrived on Sunday and the second herd, a day later. They all hung around for about two days before making their way back into the bush.”

Elephants have long been known to mourn their dead. In India, baby elephants often are raised with a boy who will be their lifelong “mahout.” The pair develop legendary bonds – and it is not uncommon for one to waste away without a will to live after the death of the other.

The first herd to arrive at Thula Thula several years ago were violent. They hated humans. Anthony found himself fighting a desperate battle for their survival and their trust, which he detailed in The Elephant Whisperer:

“It was 4:45 a.m. and I was standing in front of Nana, an enraged wild elephant, pleading with her in desperation. Both our lives depended on it. The only thing separating us was an 8,000-volt electric fence that she was preparing to flatten and make her escape.

“Nana, the matriarch of her herd, tensed her enormous frame and flared her ears.

“’Don’t do it, Nana,’ I said, as calmly as I could. She stood there, motionless but tense. The rest of the herd froze.

“’This is your home now,’ I continued. ‘Please don’t do it, girl.’

“’They’ll kill you all if you break out. This is your home now. You have no need to run any more.’

“Suddenly, the absurdity of the situation struck me,” Anthony writes. “Here I was in pitch darkness, talking to a wild female elephant with a baby, the most dangerous possible combination, as if we were having a friendly chat. But I meant every word. ‘You will all die if you go. Stay here. I will be here with you and it’s a good place.’

“She took another step forward. I could see her tense up again, preparing to snap the electric wire and be out, the rest of the herd smashing after her in a flash.

“I was in their path, and would only have seconds to scramble out of their way and climb the nearest tree. I wondered if I would be fast enough to avoid being trampled. Possibly not.

“Then something happened between Nana and me, some tiny spark of recognition, flaring for the briefest of moments. Then it was gone. Nana turned and melted into the bush. The rest of the herd followed. I couldn’t explain what had happened between us, but it gave me the first glimmer of hope since the elephants had first thundered into my life.”

It had all started several weeks earlier with a phone call from an elephant welfare organization. Would Anthony be interested in adopting a problem herd of wild elephants? They lived on a game reserve 600 miles away and were “troublesome,” recalled Anthony.

“They had a tendency to break out of reserves and the owners wanted to get rid of them fast. If we didn’t take them, they would be shot.

“The woman explained, ‘The matriarch is an amazing escape artist and has worked out how to break through electric fences. She just twists the wire around her tusks until it snaps, or takes the pain and smashes through.’

“’Why me?’ I asked.

“’I've heard you have a way with animals. You’re right for them. Or maybe they’re right for you.’”

What followed was heart-breaking. One of the females and her baby were shot and killed in the round-up, trying to evade capture.

“When they arrived, they were thumping the inside of the trailer like a gigantic drum. We sedated them with a pole-sized syringe, and once they had calmed down, the door slid open and the matriarch emerged, followed by her baby bull, three females and an 11-year-old bull.”

Last off was the 15-year-old son of the dead mother. “He stared at us,” writes Anthony, “flared his ears and with a trumpet of rage, charged, pulling up just short of the fence in front of us.

“His mother and baby sister had been shot before his eyes, and here he was, just a teenager, defending his herd. David, my head ranger, named him Mnumzane, which in Zulu means ‘Sir.’ We christened the matriarch Nana, and the second female-in-command, the most feisty, Frankie, after my wife.

“We had erected a giant enclosure within the reserve to keep them safe until they became calm enough to move out into the reserve proper.

“Nana gathered her clan, loped up to the fence and stretched out her trunk, touching the electric wires. The 8,000-volt charge sent a jolt shuddering through her bulk. She backed off. Then, with her family in tow, she strode the entire perimeter of the enclosure, pointing her trunk at the wire to check for vibrations from the electric current.

“As I went to bed that night, I noticed the elephants lining up along the fence, facing out towards their former home. It looked ominous. I was woken several hours later by one of the reserve’s rangers, shouting, ‘The elephants have gone! They’ve broken out!’ The two adult elephants had worked as a team to fell a tree, smashing it onto the electric fence and then charging out of the enclosure.

“I scrambled together a search party and we raced to the border of the game reserve, but we were too late. The fence was down and the animals had broken out.

“They had somehow found the generator that powered the electric fence around the reserve. After trampling it like a tin can, they had pulled the concrete-embedded fence posts out of the ground like matchsticks, and headed north.”

The reserve staff chased them – but had competition.

“We met a group of locals carrying large caliber rifles, who claimed the elephants were ‘fair game’ now. On our radios we heard the wildlife authorities were issuing elephant rifles to staff. It was now a simple race against time.”

Anthony managed to get the herd back onto Thula Thula property, but problems had just begun:

“Their bid for freedom had, if anything, increased their resentment at being kept in captivity. Nana watched my every move, hostility seeping from every pore, her family behind her. There was no doubt that sooner or later they were going to make another break for freedom.

“Then, in a flash, came the answer. I would live with the herd. To save their lives, I would stay with them, feed them, talk to them. But, most importantly, be with them day and night. We all had to get to know each other.”

It worked, as the book describes in detail, notes the London Daily Mail newspaper.

Anthony was later offered another troubled elephant – one that was all alone because the rest of her herd had been shot or sold, and which feared humans. He had to start the process all over again.

And as his reputation spread, more “troublesome” elephants were brought to Thula Thula.

So, how after Anthony’s death, did the reserve’s elephants — grazing miles away in distant parts of the park — know?

“A good man died suddenly,” says Rabbi Leila Gal Berner, Ph.D., “and from miles and miles away, two herds of elephants, sensing that they had lost a beloved human friend, moved in a solemn, almost ‘funereal’ procession to make a call on the bereaved family at the deceased man’s home."

“If there ever were a time, when we can truly sense the wondrous ‘interconnectedness of all beings,’ it is when we reflect on the elephants of Thula Thula. A man’s heart’s stops, and hundreds of elephants’ hearts are grieving. This man’s oh-so-abundantly loving heart offered healing to these elephants, and now, they came to pay loving homage to their friend.”